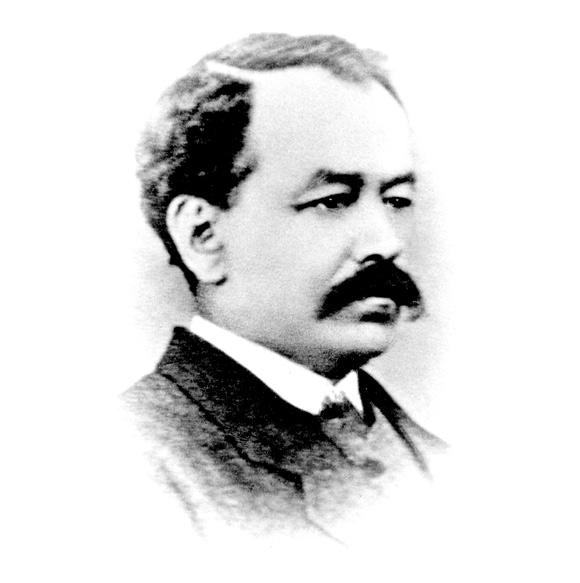

Constantin Girard-Perregaux’s brother-in-law, François Perregaux, was an adventurer born in 1834 whose sister married Constant. He learned the watchmaker’s trade before setting off for America at barely 19 years of age. After six years spent developing a watch business in New York, he returned to Switzerland.In the spring of 1859 and shortly after his return, François was approached by the Union Horlogère, a cooperative of watch manufacturers from La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle. This organisation was planning to open new trading posts in Asia, and particularly in Japan where Swiss watchmaking had not yet made an entry. In light of his experience and despite his youth, François was entrusted with this mission.

En octobre 1860, après un séjour d’un an à Singapour, François Perregaux débarque à In October 1860, after a one-year stay in Singapore, François Perregaux arrived at Yokohama, the only Japanese city that admitted strangers. A big surprise awaited him there, since time measurement in Japan turned out to be totally different from the standard timekeeping system. There were in fact two systems: an equinoctial system used by astronomers; and another referred to as civil (standard or official) time as shown on the clocks used in Japanese society.

To sum things up, the civil time system involved temporal hours: six units of equal length running from dusk to dawn and six from dawn to dusk – meaning that the length of these periods varied in step with the seasons. This implied regularly adjusting clocks every 15 days and thus 24 times a year. Moreover, the Japanese counted hours “backwards”, with the highest figure, 9, attributed to noon and midnight, and so on down to 4. Each period also bore the name of an animal corresponding to a zodiac sign (the 9 for midnight was for example the ‘rat’ period).

Japanese horologists, initiated into their art by Jesuit missionaries, thus had to build clocks taking account of these “variable-length hours” and capable of speeding up or slowing down as time went by. In most case, this involved using movements equipped with two foliots: one for the day and the other for the night. Their speed was regulated via weights that could be shifted along the foliots.

Within such a context, one might well wonder what kind of commercial success François Perregaux could have hoped to achieve with his “normal” watches. He must certainly have pondered the issue himself, shortly afterwards deciding to set up a company specialising in the production of fizzy drinks and sodas.

Nonetheless, and perhaps fortunately, a major development was to completely change the situation, when construction began on a railway network that made it necessary to establish timetables – an impossible endeavour with the system in use at the time. On January 1st 1873, Japan adopted the western time and calendar – which meant that all existing Japanese clocks and other timepieces became obsolete at a single stroke. François was thus able to begin regular imports, although he was not able to enjoy this success for very long, since the first Swiss watchmaker to settle in Japan died in 1877. He is buried in the foreigners’ cemetery of Yokohoma, where his grave can still be seen and is regularly and anonymously adorned with flowers.

Willy Schweizer is the curator of the Girard-Perregaux Heritage