The Château de Môtiers was bought in 2006 by Pascal Raffy, the proprietor of Bovet 1822. The castle overlooks the rolling landscape of the Val-de-Travers from its rocky perch. One wing of the completely restored construction, which dates back to the 14th century, houses the company’s encasing and decoration workshops, along with administrative offices. We spent a whole day there, on the first floor, discovering what goes into Bovet 1822’s watchmaking, miniature painting and engraving.

Watchmaking

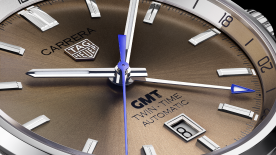

The watchmaking workshop of the Château de Môtiers is where the company watchmakers case-up, adjust and check over the haute horlogerie movements that drive Bovet timepieces. The movements are designed and developed at the Manufacture Dimier 1738 in Tramelan (in the canton of Berne), around sixty kilometres from the Neuchâtel village.

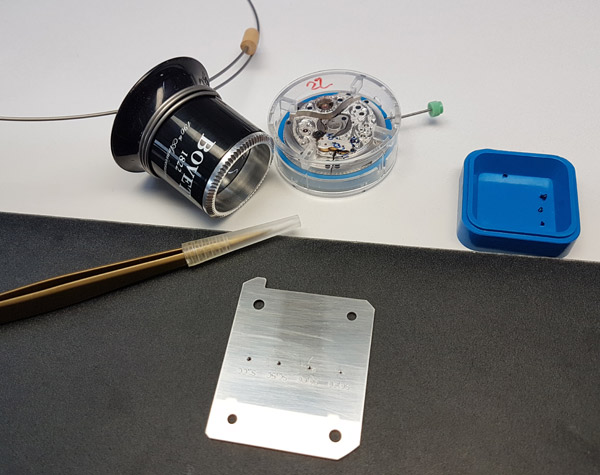

The masterclass began with a watchmaking exercise in two stages. First, four minuscule screws, all of different sizes, had to be screwed into the appropriate holes on a baseplate. It sounds a simple enough task, but in practice it proved to be the stuff of nightmares. The first step is to take up the tweezers, and then pick up each screw, ideally in the correct position to then drop it vertically into the correct hole. Patience, perseverance and calm are essential. But they are not always sufficient. Stage 1 is completed when all the screws are correctly housed or, alternatively, when they have all disappeared from the workbench, catapulted to the other side of the room after being squeezed just a little too tightly. Stage 2 was more interesting. With the aid of a diagram, the watchmaking students were required to unscrew the bridge of a movement, thus releasing the four wheels of the winding system, and then put them all back together. I completed this exercise more or less successfully, but I emerged from the ten-minute-long ordeal feeling that my eyes were ready to fall out of my head, and my hands had turned into claws, after peering through the watchmaker’s loupe and trying to pick up the tiny components.

Miniature painting

The painting exercise looked likely to be the most enjoyable, and the best calculated to restore my self-confidence. After all, we’ve all held a paintbrush, mixed colours and coloured inside the lines (our shape was a butterfly) at some point in our lives, even if that might have been back in nursery school. Clearly, no one was under any illusion that they would rival the work of our teacher, but every student was determined to create the best butterfly possible. This challenge was clearly not insurmountable. The painting master showed us his catalogue of creations: dozens of paintings, extraordinary detailed and precise, perfectly executed with the most harmonious colours. There were countless portraits commissioned by clients, both individuals and family groups, and a splendid tiger’s head.

At Bovet, miniature painting is mainly carried out on mother-of-pearl dials using the polished lacquer technique, which shares many features with Chinese lacquer painting. It allows for excellent definition of detail, and has greater shock resistance than enamel. “I use the latest-generation lacquers made in Switzerland,” explained the painter. “They are biodegradable and they have passed a number of resistance tests. One advantage of this lacquer is that it can be fired in a conventional oven, between 90° and 140° Celsius.” So much for the technical side. The artistic qualities of the painter’s creations stem from his 25 years of experience in miniature painting, and his superior draughtsmanship and knowledge of colour. Our butterflies provide a graphic illustration of just how far we have to go to reach his level.

Engraving

Bovet produced his very first watches in the early 19th century. The founder of the Maison gave new impetus to movement engraving by adding subtle details, and taking the innovative step of engraving every possible surface to create a unique three-dimensional effect. Today, the movements of all Bovet timepieces are engraved by hand. But Bovet’s three engravers also employ their art on dials, cases, chapter rings, bezels, casebands and bows. The young artisan at the Château de Môtiers who was our teacher (picture on top of the page) was trained at an engraving school, as well as completing studies in fine art, where he learned design and painting. Alongside the traditional “fleurisanne” (stylised fronds) and “bris de verre” (broken glass) motifs frequently used on Bovet timepieces, the engraver also has to be able to produce any custom engraving that might be requested by a client, whether this is a name, a portrait or a decorative motif. A chisel or burin (made by the engraver), small hammers and compasses are all essential tools. The compasses in particular are part of an artisanal tradition dear to Bovet. “When you have to decorate a case band with 24 ‘fleurisanne’ designs, a pair of compasses is essential to lay them out at regular intervals, because you can’t make any reference marks on the case,” the engraver points out.

The engraving exercise left more than one of the students hesitant and full of self-doubt. Unlike using a paintbrush, holding a burin or chisel between your fingers and applying it to a surface is not intuitive. The designs are not easy to accomplish. Engraving a simple circle is quite a feat, and it’s all too easy for the tool to skid out of control, because it’s badly positioned or you haven’t applied the correct degree of force, leaving ugly scratches. And when it comes to using the hammer on the end of the burin handle to carve small motifs, you have to be able to hit it in the right place when you have your eyes on the microscope, and you can’t see your hands. At the end of a frustrating experience, you look at the gold watch case decorated with fleurisanne tendrils placed nearby with new eyes. How on earth do they do it?