After two difficult years spent in Switzerland in the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution, Abraham-Louis Breguet returned to Paris in the spring of 1795. His company, established on the Quai de l’Horloge on the Ile de La Cité, required complete reconstruction and he spared no effort in reorganizing his workshops and winning over a new clientele. The following year, brimming with new projects and innovative ideas, he began introducing creations that are powerfully echoed in the “Tradition” line launched in 2005

The masterpiece of simplicity behind the “Tradition” line: the souscription caliber (1796)

Known for having created the most complicated watches of his era, Abraham-Louis Breguet was also the man who created the simplest watch ever made, dubbing it “souscription”.

The name of this watch is explained by Breguet himself in the brochure he had printed in 1797: “The price of the watches will be 600 livres; one-quarter of this sum will be paid when subscribing; the construction will not suffer any delay and deliveries will be made by order of subscription (…)”.

Recorded as souscription watches in the production and sales registers, they are still referred to and studied under that name by all Breguet collectors and connoisseurs.

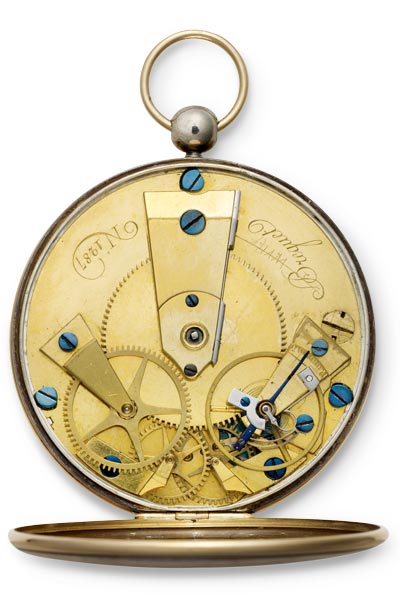

Distinguished by its large central barrel and a going train symmetrically arranged on either side of the barrel, the souscription caliber powers a single hand serving to read off both the hours and minutes and its sparing, yet surprisingly edgy design, remains as striking today as ever.

One can well imagine that Breguet was proud of this type of watch and keen to see how it would match the tastes of his contemporaries. It was, indeed, the only product for which he had a document specifically printed to outline his intentions, his motivations, and his technical choices. It is fascinating to observe how Breguet puts himself in the place of his followers, meaning his customers. This introduction took place in the wake of the French Revolution and, having spent the past two years in the safe haven of Switzerland, he had doubtless realized how much society and, thus, his potential customers had changed

The first general statement of this text notes that the accurate watches were intended “ for Astronomy and the Navy”, and that watches designed for everyday use had two main flaws: they were generally of poor quality and their price was “not within reach of a majority of citizens.” The challenge, therefore, lay in offering a model that was affordable yet endowed with a degree of robustness and precision comparable or even superior to that of watches made for scientific purposes. Breguet described these watches, based upon what he, himself, referred to as a new construction, in these terms: “They are distinguished by their simplicity and by a layout that protects the escapement from serious incidents, even if the watch were to be dropped. The going train, escapement, and regulator, the heat and cold compensator are so openly positioned and so easy to grasp that the attentive observer can see at a glance (…) the harmonious workman- ship and the reliability of its functions.” After describing the regulating components and announcing a 36-hour power reserve, Breguet also wrote that these watches would have a respectable diameter of 25 lignes (meaning 61 mm) and, surprisingly enough, only one hand – immediately adding, as if to reassure readers: “This dial size ensures sufficient distance between one hour and the next so as to mark out 12 divisions that the hand sweeps past every five minutes, and which are placed in such a way that it is easy to estimate the time to the nearest minute.”. After a very short period of time for the owner to become accustomed to the dial and hand, these watches certainly do display the time in a readable way.

The secret signature, a response to fakes

In parallel with the souscription watch, Breguet introduced another practice: that of the secret signature which the master-watchmaker – faced with a broad-scale counterfeit trade – justified in these terms. “To ensure the public is not deceived by works in which I have no part, I will put a distinctive mark on the dial, executed by a machine whose effects are extremely difficult to imitate.” The machine in question was a drypoint pantograph of which the Breguet Museum has recently acquired an historical example.

Following the French Revolution, counterfeits began to afflict the House of Breguet, a phenomenon that some may see as a reflection of an already impressive reputation, but which become more and more acute over the subsequent decades and which proved anything but a minor issue for the company at the time. The gravity of the situation is conveyed through an article written by H. Reymond in an issue of the French Journal des arts, des sciences, de littérature et de politique dated October 6th, 1809: “One cannot speak of horology without mentioning Breguet in the same breath. This artist has pushed the limits of the art to the extent that he can no longer be surpassed. (…). It is astonishing to see the quantity of watches circulating under his name, yet barely one in a thousand is actually made by him.”

The souscription watch proved a commercial success and the firm sold around 700 of them, mostly between 1798 and 1805, thereby gaining new clients who subsequently purchased more complicated models. This supremely simplified watch enjoys a rightfully earned place in the study of Breguet’s work and the maestro, in an unfinished treatise he was planning to publish, wrote at length about it in the first chapter in terms that reveal an unmistakable sense of pride. One should, however, point out that the above-mentioned total figure includes another type of model, the “tact” watch, that was called a souscription à tact timepiece during its early years.

An evolved version of the souscription caliber: the “tact” watch (1799)

Three years after developing his souscription watch, Breguet introduced his “tact” watches that provided the possibility of reading the time by touch using an outer hand and two raised markers placed around the case. In keeping with the customs of the house, these “tact” watches were interpreted through all kinds of variations, with cases that were engine-turned or enameled (in gray, blue...) and featured touch studs in gold or composed of pearls or diamonds. In his draft treatise, he explained the idea behind them. “When we imagined the one-hand watch (…) we merely aimed to build a simple, solid, accurate model at an extremely modest price; but it could not provide a service that custom and habit have rendered almost indispensable: that of audibly repeating the time, a function that was extremely useful for telling the time in the dark.”. While this read-off mode was indeed valuable when there was no light available, it also enabled the wearer to check the time discreetly without removing the watch from his pocket, thus giving a further figurative meaning to the word “tact”. These watches were also sometimes more prosaically referred to as “watches for the blind”.

Above all, Breguet saw in this new touch-based read-off system a genuine alternative to repeater watches that were both complex and expensive to produce, even going so far as to use the expression “repeating by touch”.

“Tact” watches picked up the souscription caliber in a slightly evolved form. Fitted with a mobile outer hand, some of these “tact” watches also had an extremely small dial featuring one or two hands, visible on the opposite side to that of the external arrow. It was precisely this arrangement that enabled both conventional reading of the time and a chance to admire the movement, a possibility that Breguet regarded as highly desirable and is reflected in today’s Tradition watches.

In 2005, drawing upon the inexhaustible wellspring of inspiration represented by Breguet’s heritage composed of both archives and historical pieces, Nicolas G. Hayek and the design team became convinced that this layout – possible to see from a single side that which can normally be viewed only by turning the watch over – would appeal to connoisseurs of mechanical watchmaking. That is how a contemporary wristwatch came to reprise the beautiful positioning of the central barrel as well as the symmetry of the gear trains and balance, all designed more than two centuries earlier by a brilliant pioneer of both techniques and design.

Over its first ten years of existence, the Tradition line has asserted itself through its powerful originality and has been enriched by various models, ranging from simple hand-wound or self-winding models to others with dual-time or retrograde seconds, tourbillon with fusée, independent chronograph or minute repeater functions. In each case, the effortless simultaneous view of the dial and the vital components of the timepiece proves as strongly appealing today as it did historically, especially since the gray or pink color of the movement mainplate and bridges along with the silvered or black shade of the guilloché dial heightens the contrasts and endows these models with an amazingly modern touch.

This avant-garde esthetic continues to surprise and appeal to this day through a combination of this timeless design with the constant progress being made in the domain of horology as well as sometimes daring choices. Might it not be true to say that the watches of the “Tradition” line, inspired by the finest possible sources, are to be regarded as brilliantly apt illustrations of the extraordinarily subtle alchemy inherent in contemporary Breguet watches.