In the Neuchâtel mountains, horological skills are often passed on within the family. Jean-Henri Berthoud, judge, solicitor and watchmaking-clockmaking expert trained his brother Ferdinand from 1741 to 1745. The young man then set off to complete his training in Paris, scene of the major innovations and inventions in horology, a field already combining science, technical mastery and aesthetics.

Teaching children

In the 18th century, there were very few schools in the rural communities of the principality of Neuchâtel. Tuition had to be paid, attendance was not mandatory and they were open for only a few months during the winter. While fathers were expected to provide their children with an appropriate education, they were nonetheless free to handle this themselves or to send them more or less regularly to school. For many parents, there was a great temptation to keep their offspring at home to work in watchmaking and lacemaking for a very meagre salary. Children could also be sent to printed fabric factories, where this cheap labour was always welcome.

At the beginning of the Age of Enlightenment, Jean Berthoud, an architect and entrepreneur, gave each of his sons a good education. Abraham became an architect like his father. Jean-Henri, Pierre and Ferdinand learned the watchmaking-clockmaking trade and Jean-Jacques trained as a technical draughtsman in Paris. The young Ferdinand possibly attended the small schools in Couvet, but his brother, Jean-Jacques, who was 16 years older, also played a part in the child’s education. We know that in around 1770 the latter was definitely serving as preceptor of the children of his neighbour Abram Borel-Jaquet, a clockmaker. In his theoretical publications, Ferdinand Berthoud would later emphasise the importance of being well versed in technical drawing when it came to exercising the watchmaking profession.

Acquiring fundamental watchmaking-clockmaking skills in Couvet

At the age of 14, Ferdinand began serving an apprenticeship with his brother Jean-Henri, an expert watchmaker-clockmaker. Along with the Berthoud family of Plancemont, several well-known clockmakers in the Principality of Neuchâtel were settled in the Val-de-Travers, including the Guye, Petitpierre, Borel and Bezencenet families.

At the end of this initial training, the young horologist was capable “of making and perfecting a clock”, as stated in the apprenticeship certificate he was awarded. Encouraged and supported by members of his family, Ferdinand Berthoud decided to travel to Paris in 1745. Perhaps he stayed there in the home of his brother Jean-Jacques? Certain sources mention that the latter was living in the City of Light in 1741.

Preparing to set off

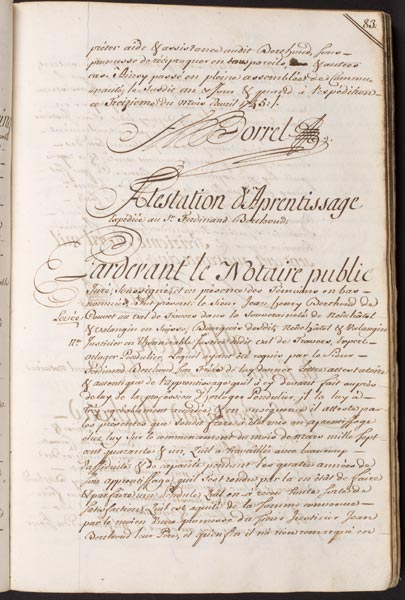

To begin the administrative procedure, Ferdinand Berthoud requested the commune of Couvet, which had convened for a regular assembly, to provide him with a certificate of birth, ascendance and good conduct. After due deliberation, he was granted this document, which specifies that he was born from “faithful marriage between parents both hailing from honourable and long-established families from this place”. The certificate was drafted by the notary Abraham-Henri Borel-Petitjaquet of Couvet, communal secretary, on April 13th 1745. That same day, he obtained an apprenticeship certificate from his brother Jean-Henri, drafted by the same notary. The master certifies that his apprentice “has worked with great assiduity and demonstrated great abilities during the four years of his apprenticeship. (…). That he has duly paid the sum agreed by the hand of his father Mr Jean Berthoud; that nothing reprehensible had been noted; and that the apprenticeship master is thus very satisfied and recommends him to any master watchmakers to whom he may turn, kindly requesting that they may provide help and support, backed by a promise of reciprocal aid in such or other cases”. A similar expression of promised reciprocity also appears on the certificate issued by the commune of Couvet. This was a very useful recommendation in light of the distrust that might arise from a foreigner requesting material assistance.

The journey

It is unfortunately not known which means of transport nor which itinerary Ferdinand Berthoud took in travelling to the French capital. Roads were sometimes very bad at the time. Nonetheless, the route from Neuchâtel to Paris was well established since the late 17th century, thanks to the pioneering Beat Fischer of Bern who had been granted permission to operate the postal service of the Sovereignty of Neuchâtel. He set up a fairly fast connection between Paris and the town of Solothurn, which hosted a French embassy. This route, organised in stages, ran through Neuchâtel and Pontarlier but was reserved for postal services and did not take aboard travellers. The latter could walk or take the “poste aux chevaux”, a term applied to private public transport companies using uncomfortable carts seating three to ten people and advancing at a slow pace or sometimes a trot. The weekly connection between Neuchâtel and Pontarlier took between 10 or 11 days to reach Paris.

The far more luxurious and fast stagecoaches appeared in the early 18th century, representing forms of public transport, which, like the royal messenger services, enjoyed the privilege of galloping along French roads. They were expensive and the price was 89 pounds from Besançon to Paris, or half that if an intrepid traveller was prepared to sit outside the passenger compartment and brave any bad weather. Meals and overnight stays cost extra.

To cover the expenses involved in travelling to and settling in Paris, Ferdinand Berthoud took out a loan with the notary Jean-Henri Jean-Henri Borel-Petitjacquet on April 16th 1745. He and his sister Jeanne-Marie borrowed the sum of 285 livres faibles (literally ‘weak pounds’, a currency used in legal transactions at the time in the region). There is no mention why the young girl was associated with her brother in this transaction. One might think she was planning to travel to Paris with him, but there is no proof of that.

By way of comparison, 40 livres faibles at the time would suffice to buy a two-year-old heifer, whereas a pocket watch with a chased silver double case cost 135 livres faibles, as mentioned in a notarial deed dating from 1731.

Jean-Henri Berthoud stood guaranteed for the loan taken by his brother and sister. Ferdinand Berthoud also gave him power of attorney to handle all his affairs in his absence. The obligation to reimburse the loan and the power of attorney document were drafted the same day and signed by the notary Abraham-Henri Borel-Petitjaquet.

In Paris, having earned the title of Master Watchmaker in 1753, Ferdinand Berthoud was to become one of the most important horology theoreticians of his era. Although he never returned to Couvet, he maintained close ties with his nephews, Henri and Louis, sons of his brother Pierre, whom he welcomed to his Parisian workshops, as well as his childhood friend Abram Borel-Jaquet, a skilled watchmaking toolmaker.

The original version of this article was published on the Ferdinand Berthoud website. WorldTempus reproduces it with the kind permission of the brand.