Talking about school in the middle of the watchmaking holidays? What a dreadful idea! Couldn’t we wait for everyone to be back at work before diving back into horological treatises? Before any of our readers relaxing on deckchairs start to get worried – what follows had nothing to do with torque theories or viscosity coefficients, but instead about brand schools.

At first glance, the two terms appear to be incompatible. School is the preserve of a public teaching mission. The brand, on the other hand, pursues individual business objectives. How can one reconcile the irreconcilable?

Somewhere between duty and obligation

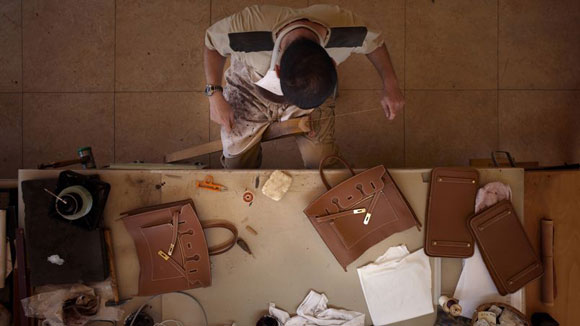

There are two predominant reasons. The first relates to duty. Over the centuries, the major brands have accumulated skills specific to themselves, tricks of the trade that are only practised within the sanctity of their own four walls. The survival of the art of watchmaking therefore depends on them teaching these to their apprentices themselves, at least when it comes to techniques that do not involve manufacturing secrets.

Only thus can watchmaking be kept at its peak. And the companies that share their heritage in this way sooner or later end up recruiting an apprentice who will dedicate these skills in their service. Under other circumstances, this would be called a return on investment.

The second reason is more pragmatic. It is no secret that academic training does not supply enough graduates to keep the industry going. Given this, what other solution is there than to create one’s own school and to train future employees oneself?

This is the solution that has been retained by a number of companies – such as A. Lange & Söhne, Glashütte Original and Hermès to name but a few. Their aim is not to replace academic curricula but to complement them. These three companies also have very specific characteristics: the first two of these embody the very essence of German watchmaking, while the third associates watchmaking skills with its original trade – namely saddlery. Thus, in all three cases, young graduates applying for jobs at these Manufactures are required to take in-house training which complements their basic knowledge and skills with aspects that are specific to the company that is hiring them.

The case of Glashütte

However, the two German Manufactures willingly proclaim another purpose: direct recruitment. “It is not easy to retain watchmaking talent where Glashütte is located in the eastern region of the former East Germany,” admits one of them. “Winters are harsh, teaching is completely in German and the immediate surroundings, Dresden, are not nearly as appealing as Geneva.”

Consequently, by starting its own school, the Glashütte Manufactures can be fairly certain that at the end of their studies, the watchmakers will remain with them.

Tino Bobe, Director of Development at A. Lange & Söhne, confirms the success of this endeavour: “We have trained more than a hundred watchmakers at our school – the Lange Watchmaking School, which opened in 1997. Their apprenticeship takes three years. Since then, almost all the students have remained with us.”

At Glashütte Original, the pattern is similar, as is the success. “We started out with 12 students and currently have 24, in addition to four future toolmakers,” the Manufacture confirms. “The training takes three years and the best students with Merit and Distinction grades are guaranteed an immediate job with Swatch Group.”

In France, Hermès is doing the same thing with its leather trades. The company mainly recruits talents from the prestigious Ecole Boudard de Montbéliard and continues their training in-house over several years.

Moving towards privatised teaching?

Above and beyond this idyllic picture, this situation raises a certain number of issues. The first relates to the number of graduates produced by the academic circuit, which is inadequate. This is one of the reasons behind the development of these private schools.

It must however be said that with increased funding, the Swiss WOSTEP and French watchmaking schools would be able to welcome more students. If the means the Manufactures are currently devoting to their own schools were partially rerouted to supporting public education, student numbers could probably be increased.

Moreover, with regard to the quality of teaching, the Manufactures could supply some of their skills to the core curriculum of academic watchmaking subject matter. Why not create a “German watchmaking” module as part of the traditional curriculum? Or a course on “bracelet/strap-making trades”?

Current teachers would say that with nearly 3,000 hours of courses to teach over two years, one cannot do everything. While that is certainly true, an additional year remains a possibility. At the moment, nobody can blame the Manufactures for having indulged in a form of privatised teaching – an approach that is undeniably preserving the very essence of the watchmaking art.