The first 20 years of this century saw innovations in watchmaking on an unprecedented scale, in particular when it came to the materials used to make watches. Materials were developed, converted, and diverted from their original uses for the purposes of watchmaking. Spurred on by the quest for performance, differentiation and prestige, watchmakers enlisted ingredients that were lighter, stronger, more luxurious and above all more technical. Pioneering brands such as Audemars Piguet, Richard Mille, Hublot, IWC, Panerai and Ulysse Nardin have been at the cutting edge of such approaches, making the most of technological progress by incorporating it into a broader rationale characterised by open-mindedness, narrative, design and identity.

Opening Up

Up until the turn of the millennium, the catalogue of materials used in mechanical watchmaking remained largely unchanged – and, more importantly, compartmentalised. Steel and gold were reserved for cases; titanium began to be used, too, as did platinum on rare occasions.

The appearance of these materials could be altered using rudimentary veneering techniques. Movements, meanwhile, were made of brass or steel, with the very occasional use of a few synthetic materials. Crystals were made of transparent polymer or sapphire. However, this neatly organised landscape was to change out of all recognition with the sudden advent of new sources of supply – and new ideas. By connecting with specialists from the worlds of aerospace, medicine, microelectronics, automobile and heavy industry, the watch broke free from its intellectual shackles, with an ensuing impact on its exterior components and movement alike.

Featherweight

One of the quests that bore the most fruit was the search for lighter materials, with titanium, aluminium and a whole host of composite materials coming to the fore. Research also exploited the properties of structures that were more resistant to bumps and scratches, such as carbon, fine alloys, and so-called technical ceramics. The related investigations resulted in a plethora of surface treatments such as PVD, DLC, and ceramised surfaces. In addition, the high-end aspect of the business encouraged diversification along other, similar lines, with the use of exotic metals such as tantalum and palladium; while hard and semi-precious stones made a comeback, too. Extreme high-tech also became synonymous with prestige, as can be seen from the various new uses to which sapphire and silicon were put.

Metal

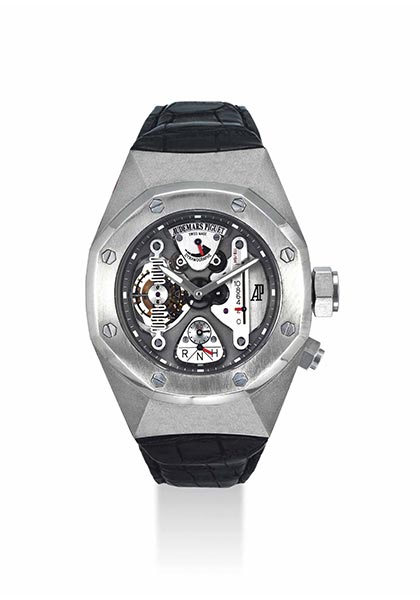

The material that really ignited the trend was titanium. Having been used by pioneers in the 1980s and 90s, it was to take off with a vengeance during this period: a case study in the route taken by materials from outside the watchmaking world right to its very centre. Indeed, many materials and techniques used for watch components derived from another specialist trade in Switzerland – the dental industry, which also uses titanium for its lightness, hardness and perfect compatibility with human skin. This metal proved to be particularly technical – and suitable for combination with other metals, including magnesium, aluminium and zirconium. Alloys became so promising that some brands went so far as to make them part of their identity. By giving alloys names like Zenithium and Hublonium, firms basked in their reflected high-tech glory. Others were (slightly) more modest, adopting exclusive names exuding technical prowess, such as Harry Winston’s Zalium. Lightness, hardness and a dark grey appearance served as markers, reminding the public just how vast and fertile alloy science is. And so it was that the strangest of materials took centre stage, among them the Royal Oak Concept’s Alacrite, Maurice Lacroix’s Powerlite, and AluSiC, imported from the aerospace industry by Richard Mille.

Synthetics

Composites offer another way of making the most of the disparate assets of different materials. These technical plastics are made from a resin composite with varying degrees of hardness coupled with a filler material. PEEK is an iconic composite: being extremely hard and reinforced with carbon fibres, it has proved to be versatile – and offer a wealth of inspiration. The woven fibres form sheets that can be moulded before being cured. The process, also present in the world of motor sport, is used to produce cases and dials in a material with a regular structure. Above all, though, carbon is used for its lightness and resistance to torsional forces.

It is added in very thin successive layers, in different directions, vastly increasing its natural strengths and giving it a variegated appearance. Richard Mille has worked in partnership with sail manufacturers North Sails to use North Thin Ply Technology (NTPT™), in which hundreds of layers are set in a solid binder and used as a raw material. The materials are processed using ordinary machining robots to make plates, bridges, and crowns – more especially, ultra-light cases that are stretch-, impact-, and scratch-resistant, as well as being non-magnetic. Nor is it technical qualities along that have led to new materials finding favour.

Vintage watches were to have such a strong influence that after being absent for quite some time, bronze began to be used in watchmaking once again. The fact that bronze oxidises, and thus develops a patina, was transformed from a crippling weakness into a selling-point by Panerai with their PAM 382 Bronzo.

Polymorphous

The other material that saw an unprecedented boom was a ceramic, zirconium oxide, also known as zirconia. After being introduced by IWC with its black or white ceramic Da Vinci, then having been imported from the space industry by Rado in 1990, it was popularised by Chanel’s J12, before going on to conquer every corner of watchmaking. Zirconia can be found in the movement, where its low friction properties make it a great replacement for jewels, and in the ball bearings beneath the rotors. Decoratively, zirconia came to be used in cases, crowns, bezels, casebacks and even bracelets.

Ceramics are indeed light, biocompatible, rustproof, non-magnetic and comfortable to wear – attributes that are virtually unparalleled in terms of comfort. What’s more Rado succeeded in dyeing ceramics in every hue. They are suitable for high-performance applications, too, like the very sturdy boron carbide used by IWC. Most amazing of all is their link with titanium or aluminium alloys. Panerai began cutting components from this metal and then treating them using a surface ceramic process. The result is a lightweight, solid core that is hard and dyed on the outside, rivalling the star of surface treatments, PVD. Originally designed for hardening cutting instruments, PVD technology involves adding a series of hard, thin, and highly adhesive layers: it led to the huge ‘black watch’ phenomenon. As an added bonus, PVD went on to be applied almost everywhere, from the case to the visible components of the movement.

*On the occasion of GMT Magazine and WorldTempus' 20th anniversary, we have embarked on the ambitious project of summarising the last 20 years in watchmaking in The Millennium Watch Book, a big, beautifully laid out coffee table book. This article is an extract. The Millennium Watch Book is available on www.the-watch-book.com, in French and English, with a 10% discount if you use the following code: WT2021.