Sitting talking to Guy Semon, the mathematician who heads up the TAG Heuer Institute, across a desk strewn with technical journals and a huge tome on carbon nanotubes, you sometimes have to pinch yourself to remember you are at the TAG Heuer HQ in La Chaux-de-Fonds rather than some university. Yet as a Frenchman who hails from the Doubs region of France, which saw its watch industry die out in the short space of a few years, he is acutely aware of the impact that technological developments can have on the industry. He is now using just such a technological development in search of growth in a sluggish market – by capturing market share from his competitors.

Mr Semon has a gift for making even the most complex subjects readily understandable, even if the explanations are sometimes accompanied with mathematical comparisons. Faced with the challenge of coming up with something different from everyone else, he quickly settled on the regulating organ, dismissing the power reserve (too many constraints) and the gear train (there will always be 60 seconds in a minute and 60 minutes in an hour – you can’t change that). More specifically, he focused on the hairspring.

“I decided to look at what the mathematical limits of precision for a spring were,” he says, “but there are challenges here, too, because springs are very difficult to produce and require about 20 different operations. Their frequency is also directly related to their stiffness.” Silicon could have been an option, but Patek Philippe, Rolex and the Swatch Group have together sealed off that avenue. “We could have made it ourselves,” he adds, “but it would have taken us a couple of years and we would have just ended up with the same thing as the others, only it would have been more expensive. And I am here to make the difference and to do that we look into areas where other brands haven’t ventured.”

To be sure, no other brand can be looking into areas where TAG Heuer is. The TAG Heuer Institute consists of 24 people from 11 different nationalities and together they have academic experience totaling 250 years. Only one of them has a watchmaking background. They are there to push the limits and challenge the impossible, to such an extent that they all have a piggy bank on their desk where they have to put five francs every time they sigh or say that something is too complicated or impossible. Guy Semon says the fine will soon rise to 10 francs…

The Institute consists of four departments, working on metals, compliant mechanics, nano-materials and the industrialization of any technology developed by the Institute. The new balance spring is the work of the nano-materials department which, as Guy Semon poetically puts it, “tries to talk to the atoms... But first we have to catch them.” Catching them involves using a three-million Swiss franc scanning electron microscope (SEM), which is impressive in itself. But the Institute will very soon take delivery of a colossal 4.3m high transmission electron microscope (TEM) that can only work with zero vibrations. The road outside the factory and the nearby overhead railway cables would be enough to disturb it, so a giant hole several metres deep was excavated right underneath the room where it will be installed and filled with 26 tonnes of concrete to form a solid foundation.

The inspiration for the new carbon spring came from graphene, which was discovered – by chance – in the 1990s and has hexagonal bonds that make it the perfect spring. It returns the energy it absorbs as it jumps back into place. The only problem is that this only worked at the atomic level and what happens at atomic level can never be replicated at the “macro” level of real-world applications... until now. The TAG Heuer Institute is the first to develop a mechanical structure from an atomic structure.

Chemical reaction: How the new carbon spring is made

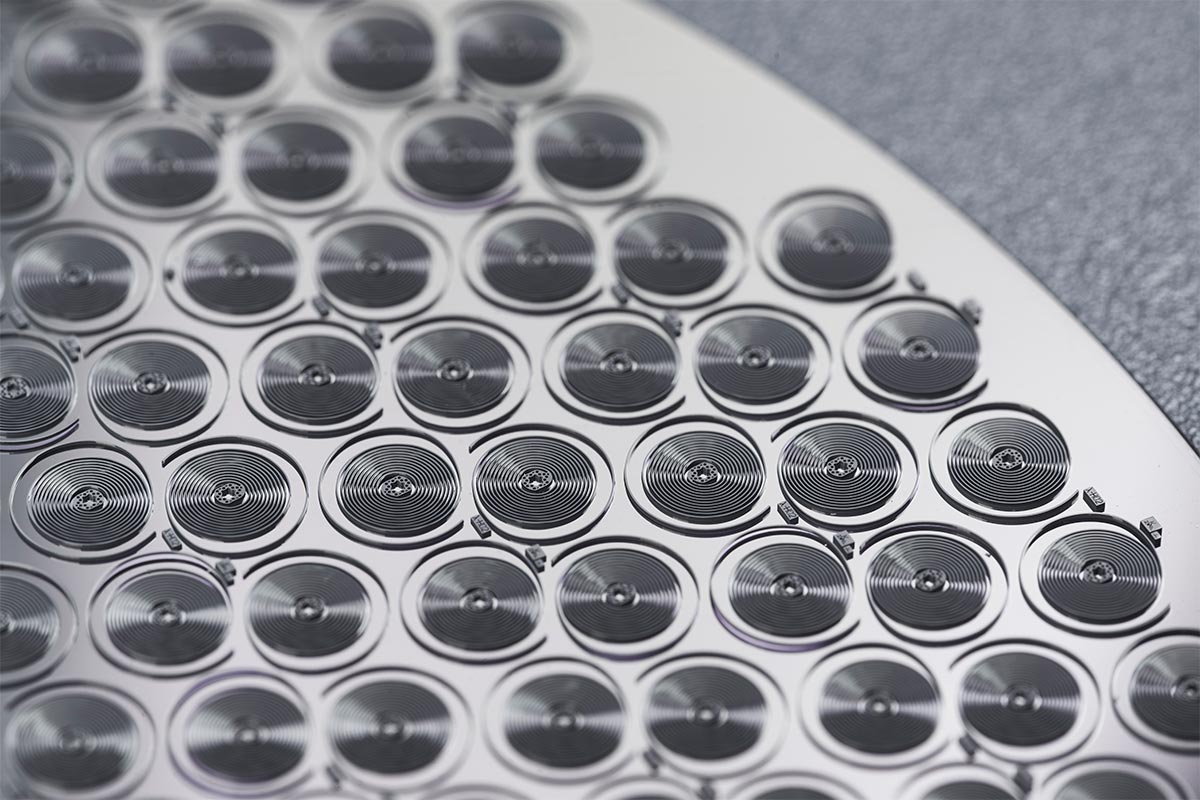

With the theory for the material in place, the first step was to develop software to calculate the perfect geometry for a spring (using Young’s modulus). From that, drawings were produced and used as a basis for creating a “mould”. In this case the mould is a silicon wafer (because silicon is chemically neutral, clean and flat).

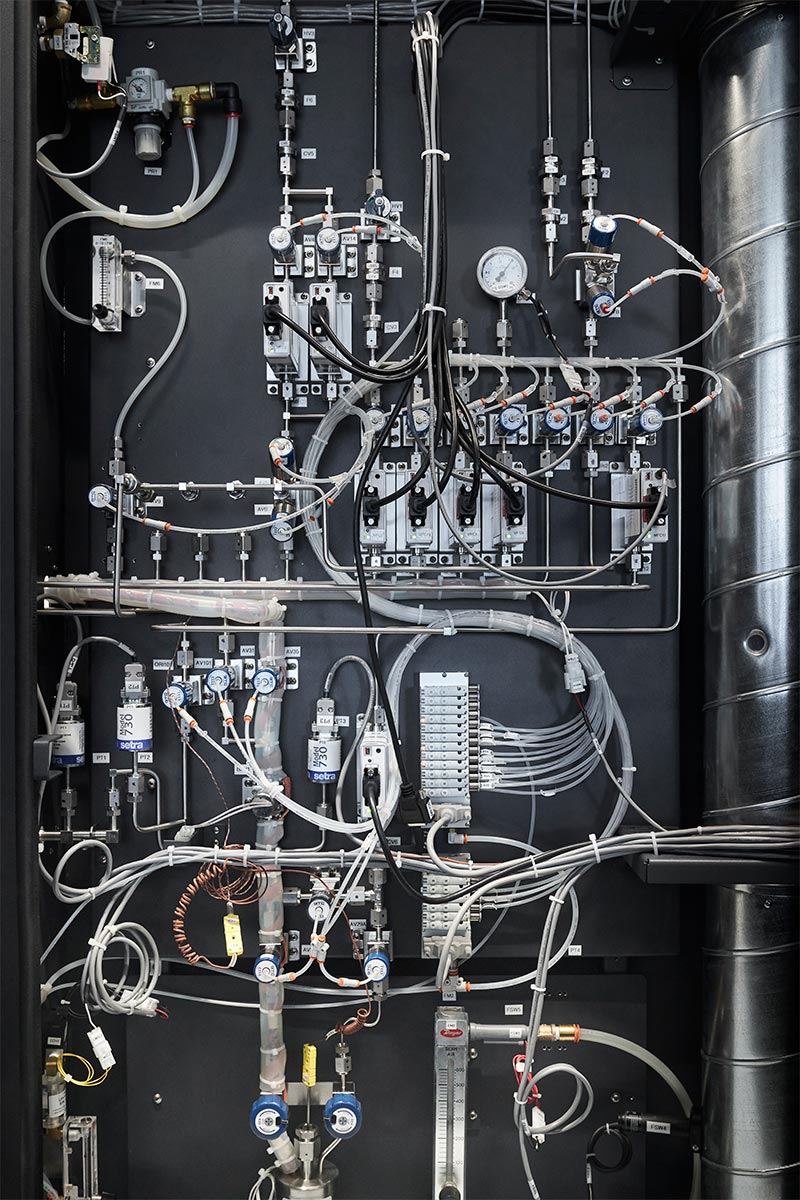

In the next step, what Guy Semon describes as an “atomic pencil” is used to draw the outline of the spring on the wafer in iron atoms. This is all done in a specialist clean room in Holland. Once these wafers arrive at TAG Heuer in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the first step is to remove any traces of oxygen (the presence of oxygen means the possibility of oxidation, or rust).

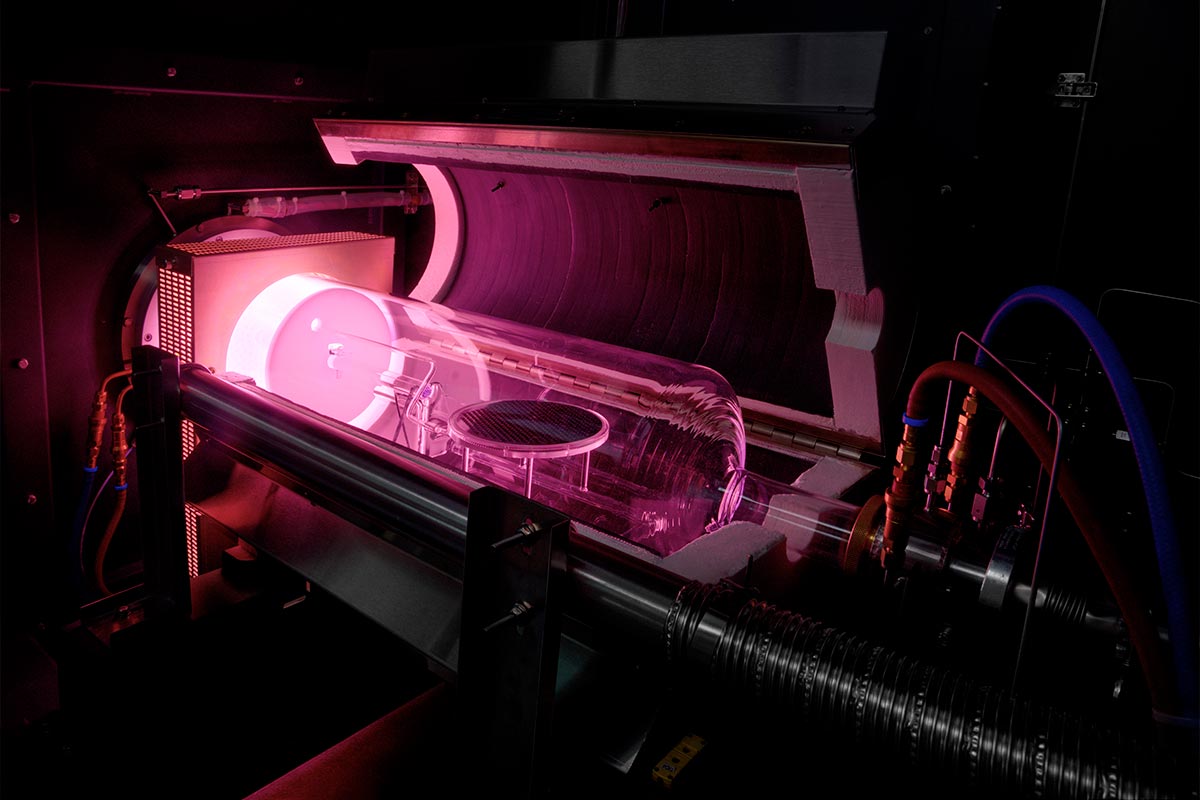

The wafers are then heated to 900°C in a quartz tube into which a mixture of hydrogen and ethylene is injected. Ethylene is used because it is rich in carbon atoms (its chemical formula is C2H4) and carbon is not usually available in gaseous form. The hydrogen atoms in the ethylene naturally bond with the atoms in the hydrogen, leaving the carbon atoms “excited”, since they are not in their natural state. Since all elements tend to return to their natural state, the carbon atoms need to bond. “Normally they would bind together to form graphite, but we don’t want that,” explains Guy Semon. “That is why we use the iron atoms, because they are a natural catalyst.”

After this first operation, 96% of the resulting material is just empty space, which Guy Semon compares with a forest at atomic level. Carbon atoms are inserted into the spaces between the atomic trees to form a composite material. All this is done without any human intervention whatsoever, which has led to the internal nickname of “cadabrium” for the material, from the “abracadabra” used by magicians.

Each silicon wafer can hold up to 400 individual springs. It takes several hours to produce one batch and the only two machines of their kind in the world that can do this are right opposite Guy Semon’s office.

Once the springs are ready, the wafers are put into a plasma cleaner to remove any carbon film, after which the springs can simply be pulled off the wafer with tweezers. TAG Heuer currently has the capacity to produce about 100,000 springs per year, but is working on increasing the size of the wafers and stacking them vertically in the machine (at the moment, only one wafer at a time is used), which could triple this capacity.

The terminal curve is preformed and the thickness of the spring actually changes from the perimeter to the centre. The collet at the centre of the spring can be produced in any shape and TAG Heuer has taken advantage of this to incorporate the brand’s shield emblem which, at just 15 microns in size, is a fantastic anti-counterfeiting measure.

The future

TAG Heuer has already produced tens of thousands of these springs, which can withstand forces of 5,000g without breaking – much more than any other spring. Guy Semon is already working on the next steps. “Now we need to explore this forest, which is why we have the electron microscope. No other watch brand has anything like this.” Given the brain power inside the Institute and the fact that this major new development took a relatively short three years from idea to fruition, we can expect much more to come from the TAG Heuer Institute.