While people often rave about the beauty of a dial, the slenderness of a hand, the clarity of a sound, one virtually never hears any such praise of the watch case. In its defence, the name itself does little to help. The word ‘case”’ (or boîte in French which can even mean ‘box’) evokes a technical element, a container. Other prettier names might enable it to attract more attention, because who is going to take much of an interest in a mere “case”?

Materials: in search of the original and even the impossible

Back in 2013, Roger Dubuis, which likes to spring mechanical surprises, struck an impressive blow where it was least expected by introducing a superlative case construction for a no less singular watch: the Quatuor.

Since the 2000s, silicon had already been used for watch components, and Roger Dubuis decided to make a case from this material. The French company Hardex was entrusted with handling this eight month-long project. The Quator case continues to exude a uniquely deep and intense grey radiance. Three of these watches were to be produced, along with three others destined for customer service.

Somewhat less extreme than silicon, titanium cases are notably offered by De Bethune. “This material is hard to machine because it heats up very quickly”, says Denis Flageollet, Director of R&D. “And as we’ve chosen to work only with polished titanium, the work takes even longer to complete. “

Shapes: revealing all, with or without drilling!

In terms of shapes, one might be tempted to say that just about anything goes, and designers certainly seem to feel that way. But when it comes to execution, it’s a whole different story. “We do exactly what we shouldn’t,” quips Stephen Forsey of Greubel Forsey. “For each new model we create, we make a new case. And if possible we like to drill in places where it should be left intact…”.

Behind the joking manner, Stephen Forsey is in fact addressing the issue of the openings in the sides of the brand’s tourbillon models, designed to facilitate admiring their beauty. This is a praiseworthy but technically difficult idea, since drilling a case considerably weakens its structure and reduces the range of techniques that may be used to machine it. As if to drive his point even harder home, Stephen Forsey adds: “Our lugs are also add-on components; you will never see the other holes we had to drill in order to insert the screws required to secure them in place!”.

Integrating the glass and the lugs is thus clearly one of the sensitive issues in making a case. In speaking of the HL2.0 watch, Hautlence CEO Guillaume Tetu admits that its case is “one of the most complex on the market, while remaining wearable. Both the shape and finishing called for a unique construction with crystals glued and carved from a sapphire crystal – all within a vertical tonneau shape featuring a drawer-type caseback at 3 o’clock and a double curvature.

At the end of the day, machining is definitely the thorniest issue when it comes to cases. As the co-founder of Urwerk, Felix Baumgartner, points out: “a standard round case calls for 8 hours of CNC programming, 4 hours of adjustment and 30 minutes of actual execution, whereas an UR 103.03 model implies three weeks of CNC programming, a week of adjustments and seven hours of machining for each case”.

A terrifying prospect? Quite likely, and definitely what led Christophe Claret to internalise case construction. “It was unthinkable for us to make such complex movements and then find ourselves stuck because nobody was able to make what I’d requested!” says the watchmaker. Today, the Manufacture is probably the most advanced among its peers in this respect. It was the first to have 16-axis CNC equipment to machine its cases; the first to introduce a sapphire case – which also happened to be tubular – almost 10 years ago. Not to mention other firsts. Extremist and perfectionist by nature, Christophe Claret no longer faces any technical limits when it comes to case-making.

Other-worldly cases

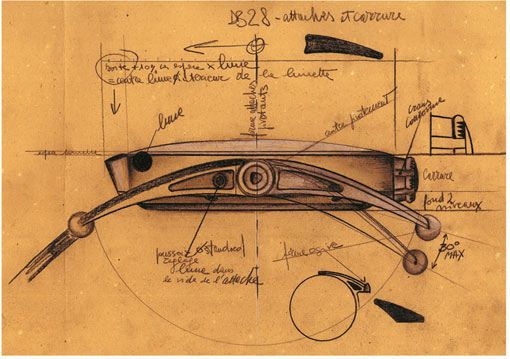

Denis Flageollet is no slouch when it comes to watchmaking vessels. The brand is the brains behind floating lugs, a highly distinctive case construction model enabling optimal adjustment to any kind of wrist. First introduced with the Dream Watch 2, this element is now patented and picked up on a number of the brand’s timepieces, including the DB28. Hysek’s mobile lugs are indeed based on a somewhat similar concept.

However, De Bethune did not stop there when it came to cases. “The DB29 is the first wristwatch to feature an officer-type back with an entirely invisible hinge. Our goal was to preserve the smooth line of the case middle while avoiding the visual disturbance caused by a protruding hinge,” explains Denis Flageollet. Patek Philippe has in turn offered its own interpretation of this principle in 2013 within its Calatrava collection.

Louis Moinet quickly established itself as a proponent of highly technical watch case constructions. The basic structure already comprises almost 50 parts, including a patented winding-stem protection system. The case of the Jules Verne steps things up a notch with 82 parts and an built-in double chronograph lever system.

Finally, DeWitt has also created the incredible X-Watch, fitted with an articulated X-shaped cover partially concealing the dial of the watch. This system is activated by four pushers located on the lower and upper parts of the case. Pressing these pushers causes the X to split in the middle into two sections, thus revealing the dial beneath.

The jewellery factor

Jewellery watches involve other types of constraints. In this domain, techniques are not the issue and aesthetic appeal rules supreme. Jaquet Droz has taken this principle to its ultimate conclusion with its Lady 8 – a model adorned with a figure 8 of which the lower part actually contains the watch and the upper part a gem. The brand is betting firmly on the case of this timepiece to ensure the anticipated success. The Cartier Crash watch is another example of a case featuring completely original shapes.

DeLaneau has opted to highlight the complementary nature of artistic crafts and design. The shape of its cases has become its aesthetic signature. Atame and Dôme are the most eloquent examples of this approach and feature arch-shaped lugs visibly passing through the curved and gem-set cases.