Of all the Bonaparte family, Caroline Murat (1782-1839) was Breguet’s most loyal patron. The youngest sister of Napoleon I, she bought her first Breguet timepiece in 1805, at the age of 23, and would continue her purchases at an impressive rate until 1814. Indeed, the company sold no fewer than 34 watches and clocks to her who, in 1800, married Joachim Murat, then a commander of the consular guard. They ruled as King and Queen of Naples from 1808 to 1815. Throughout her turbulent reign, Caroline Murat fostered the arts, oversaw the decoration of the royal palaces, took a personal interest in the archaeological excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, and encouraged manufacturing. She introduced Naples to French painters, among them Ingres, and craftsmen of Parisian fashion, theatre, and… watchmaking.

Evidently, Caroline was enamored of fine watches, and a particular admirer of those which left Breguet’s workshops on Quai de l’Horloge. This was something of a family trait, as Breguet’s archives for the Napoleonic period are replete with the names and titles of her siblings: Napoleon himself, who acquired three timepieces prior to embarking on his Egyptian campaign in 1798, and his consorts Joséphine from 1797 and then Marie-Louise from 1811; Joseph, King of Naples and later Spain; Louis, King of Holland; Lucien, Prince of Canino; Jérôme, King of Westphalia; Pauline and her husband Prince Borghese; Elisa, Grand Duchess of Tuscany… not to mention their relations and high-ranking dignitaries. The imperial family’s purchases warrant a study in their own right!

Indeed, closer analysis of these various purchases reveals a curious incident spanning the years 1810 to 1812, involving our very own Caroline Murat and… a wristwatch.

A wristwatch in this era? Impossible, say some. Much too soon, say others! Indeed, the wristwatch made its timid debut around 1880, first for ladies then a little later for men as, circa 1910, cyclists, horse-riders, and pioneers of aviation and automobiles took to the wristwatches that now featured, in one or more versions, in every watchmaker’s catalogue. All of which is a long way from our story! But as with any invention, there are always antecedents, prior occurrences which have been forgotten or are known only to specialists.

Leaving aside records of watches which were later worn as charms on bracelets, or mounted in or hung from wide bracelets, we shall concern ourselves only with watches that were, from the outset, intended to be worn on the wrist. For a long time, Patek Philippe of Geneva claimed an important first in this domain with “the request, in 1868, by the Hungarian Countess Kocewicz for the first veritable bracelet-watch.”

Pendant son règne à Naples, Caroline Murat encouragea l’art sous toutes ses formes, assurant la célébrité de nombreux artistes tant français qu’italiens.

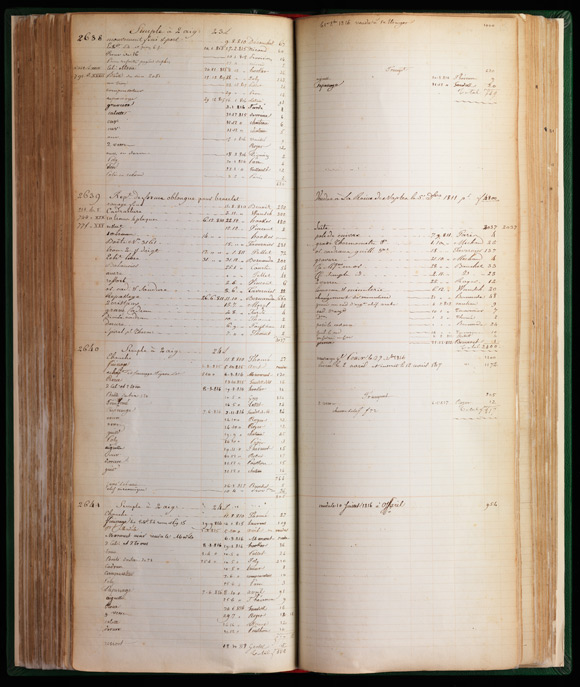

Breguet’s watch for Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples, came some 60 years earlier. But what do we know of this improbable story? What do the archives tell us? Let’s travel to Paris where the historic archives of Maison Breguet are preciously conserved at Place Vendôme. The register of commissions, as they were already known, lists the special orders placed by customers who had failed to find their heart’s desire among the timepieces proposed. This fascinating book is filled with all manner of complications and fantasies which Abraham-Louis Breguet agreed to make for his patrons, among them many powerful and famous figures. on page 29, we learn that the Queen of Naples placed an order on June 8th 1810 for two unusual timepieces: a grande complication carriage watch for the sum of 100 Louis, “in addition to a repeater watch for bracelet for which we shall charge 5,000 Francs.” This astonishing order reap- pears in the manufacturing register, which presents each watch’s detailed identity and a complete summary of every stage in the making of the piece.

The Queen of Naple’s commission becomes watch N° 2639, with the unprecedented description, “oblong repeater for bracelet.” It went into production on August 11th 1810, just two months after the Queen had placed her order, and was completed on December 21st 1812. Thus it took almost two and a half years to make. We learn that this was a repeater watch, specifically a quarter-repeater which is common for a Breguet timepiece. Far less common is its oblong, that is oval, shape. The manufacturing register informs us that the watch incorporated a lever escapement and a thermometer. Seventeen people, all named, were involved in its manufacture which required 34 separate operations. By early December 1811, it seemed the watch was ready. on December 5th, an invoice was drawn up for 4,800 Francs. Not only did Breguet keep to his original quote of 5,000 Francs, he even took 200 Francs off the price!

And yet it was a further year before the watch left Breguet’s workshops. Apparently, Abraham-Louis Breguet had decided to postpone delivery. For a watch to be presented to its owner, each detail had to be perfect. That was the rule. First the motion-work system was replaced; either it wasn’t entirely satisfactory or had broken. Then, no doubt at the Queen’s request, the guilloché gold dial was replaced by a guilloché silver dial. The register notes the dial had Arabic numerals, which were common on an enamel dial but extremely rare on a gold or silver dial. The watch was finally ready on December 21st 1812. No doubt it was sent to Naples where Caroline had taken the throne in place of Murat, who was fighting alongside Emperor Napoleon in Russia. There are no sketches in the archives to indicate its exterior. Fortunately for us, the watch appears in 1849 in a register of repairs carried out on Breguet watches; what we now call after-sales service. An entry dated March 8th 1849 notes that Countess Rasponi, “residing in Paris at 63, Rue d’Anjou,” had sent watch N° 2639 for repair. The countess was none other than Louise Murat, born 1805, the fourth and last child of Joachim and Caroline Murat, who in 1825 married Count Giulio Rasponi. The watch is described in detail: “Very thin repeater watch N° 2639, silver dial, Arabic numerals, thermometer and fast/slow indicator off the dial, the said watch is mounted on a wristlet of hair woven with gold thread, simple gold key, a second wristlet, also woven with gold, in a red leather case. For repair.” We can thank the author of this text, no doubt amazed by such a rare object, for providing such precise details. The watch was returned to its owner on March 27th 1849. The repairs, which cost 80 Francs, were as follows: “We polished the pivots, reset the thermometer, re- stored the repeater to working order, overhauled the dial, cleaned each of the parts and adjusted the watch.” It was again brought in for repair in 1855, which is the last trace Breguet has of it.

Today, the Queen of Naple’s watch is nowhere to be found. No public or private collection lists it on its inventory. Does it still exist? Will it one day reappear? Investigations are under way!

Archive descriptions give a fair idea of the watch and, despite missing information (size, exact configuration of the dial, shape of the bracelet, attachment and fastening), such a work of art, such a feat of achievement, leaves us in awe.

Based on what we do know of this watch, we can only pay homage to Abraham-Louis Breguet who, in response to a request made by the Queen of Naples on June 8th 1810, imagined specifically for that purpose the world’s first known wristwatch; a timepiece of unprecedented construction and extraordinary refinement, namely an exceptionally thin, oval repeater watch with complications, mounted on a wristlet of hair and gold thread. We can also pay tribute to Caroline Murat, a true admirer of timepieces without whom Breguet would perhaps never have created such an object. Few people are aware that, had Caroline accepted the Principality of Neuchâtel proposed to her by her brother in 1806, she would have reigned over a country of watch- makers. She declined, on the grounds it was too small. But we can’t rewrite history.

This article is reproduced from the magazine Quai de l’Horloge with the kind permission of Breguet. You can see past issues of the magazine the Breguet website or access the magazine from your iPad using the Quai de l’Horloge application from Breguet.