How can one write history without a document? What would an historian do without the sources that are his key priority and very reason for being? Be it about a character, a place, an invention, a civilization or a company, what could one write without sources?

In the case of Breguet, which has manufactured timepieces without the slightest interruption since the last quarter of the 18th century, an invaluable archive has survived right up to the present, carefully preserved and maintained in Paris, today at the flagship boutique on the Place Vendôme.

This document collection, which is probably a model in its own right, can be classified into several distinct families.

The production registers chart the details of the construction of each watch with the date and the cost of each operation as well as the names of all those involved. These registers cover a period from 1787 to the mid-19th century. They make it possible to trace the time taken to produce a watch from the moment the movement ébauche or “blank”receives the individual number that will become in some way its “identity card” right the way through to the final operations prior to delivery to the client. Everything is numbered, from the ébauche to the presentation box and including the gear trains, the dial, the hands, the case as well as the various adjustment operations. Certain elements are very expensive, such as the cases that frequently represent up to a third of the retail price of the finished watch and more than double the price of the ébauche. The production time naturally depends on the degree of complexity of a given model, but overall one observes a steady decrease over the decades. Whereas at the beginning of the Empire it took around two years to create a classical piece, be it simple or a repeater, by 1820, one could make the same piece with a lead time of between 12 and 15 months. We are aware that Breguet has always invested a great deal in organizing and rationalizing its work. The time it takes to manufacture each watch is, therefore, known. As an example, the attractive Duc de Frias moonphase watch, the Breguet n° 3066, which was featured in 2009 on a poster at the entrance to the Louvre Museum exhibition, was begun on January 15th 1817 and finished on December 16th 1818.

The mention of those involved in producing the watch provides an opportunity to learn the name of Breguet’s employees as well as its suppliers. We thereby know the identity of its ébauche and gear train suppliers (Decombaz, Sandoz, Benoit, Petremand, Laloë, Vuitel and certain others), but also that of the case manufacturers (the famous quartet consisting of Gros, Mermillod, Joly and Tavernier), as well as the hand-makers (mostly Thévenon but also sometimes Albertine Marat, the sister of the famous revolutionary), etc. Through these annotations one can track how many years one or another watchmaker worked with the company. All the watchmakers who worked for the company, whether at the Quai de l’Horloge or from home, were paid ‘per piece” and did not receive a regular salary. Their pay reflects the exact amount of work they performed, as recorded in these vital company registers. A.-L. Breguet had high expectations of its employees but was ready to reward them for exceptional work. In these cases, a family tradition has it that the founder used his fountain pen to add a little tail to the last zero and thus make it a nine. In the same way, 100 could be turned into 109!

In addition, information supplied in the records makes it possible to know both the exact cost price of the watch and its retail price to the client. In this way one can calculate the profit margin that Breguet wished to make. It is based on this margin, and this alone, that Breguet kept his company going, paid its administrative and operational costs, funded projects and earned a living for himself and his family. One can see that the margin varies depending on the complexity of the models. As an example, a silver “subscription” watch carried a cost price of 450 francs and a retail price tag of 600 francs (cost +33.5%), while a classic repeater watch involved a cost price of 1310 francs and sold for 1800 francs (cost +37%). For certain pieces however, that were both luxurious and unequalled by competitors, such as the perpétuelles watches, Tourbillon watches, tact watches decorated with diamonds or sympathique clocks, Breguet carved out far higher margins ranging from 65 to 135%.

These registers are clearly a true mine of information …

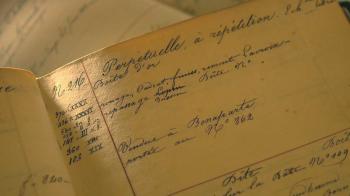

Sales registers make it possible to track the sales of all Breguet watches through their individual number. These registers, sadly lacking from 1787 to 17909, are complete from 1791 to the present day and constitute an invaluable asset. Each annotation includes the individual number of the watch, a short description of the piece, the date of the sale, name of the purchaser and the price. Where relevant, the annotation is completed with repair numbers that refer to repair registers. Thus, through the successive repairs mentioned, one can retrace a watch’s journey and its different owners through several generations. From around 1845, the coexistence of the manufacturing registers and the sales registers, which are a simplified version thereof, were to disappear, making space for a single type of register – namely sales. It is this type of register that still exists today. In fact, in the digital era with its ever more swiftly evolving media options – none of which may still be readable in 50, 100 or 150 years – Breguet has decided to print the contemporary production on paper and with good quality ink. In this way, the same level of information as was available in the past will enable people in the future to follow the life of the Breguet company in the late 20th century and early 21st century. The contrary would have been unthinkable!

Repair registers contain precious information. Breguet has always recommended and still recommends that its clients have their watches repaired or serviced by Breguet. Right from the start, the workshop earned such a great reputation that it repaired watches from all brands and all countries. The oldest repair register preserved starts on December 5th 1791, and the time-consuming tradition of noting each repair in a book lasted until the beginning of the 1970s. The oldest registers cover a period right in the middle of the French Revolution. They are scattered with names such as Marie-Antoinette for her n° 46 perpetual, Axel de Fersen for his Swedish-made military watch, Madame the King’s sister-in-law (the Countess of Provence, wife of the future Louis XVIII) for her N°27 perpétuelle watch. The greatest names in France rub shoulders here. However, the pace of events accelerated and the way clients’ names were mentioned also evolved rapidly! The Princess of Monaco becomes “Madame Monaco” and the Duke of Praslin becomes “citizen Praslin”.

A few years later, old titles were to reappear along with completely new ones under Napoleon’s rule. The Breguet archives were a directory of a perpetually renewed high society. On the sociological front, they thus also provide a wealth of information…

These three types of registers make the Breguet archives unique in terms of their coherence and of the exceptionally long period that they cover with no missing years. Sadly, the destruction and pillaging of the workshops that took place in 1794 during the Revolutionary Terror has deprived us of part of the registers between 1787 and 1790 (sales could be reconstituted from 1791) and virtually all the documents regarding the company’s early days from 1775 to 1787.

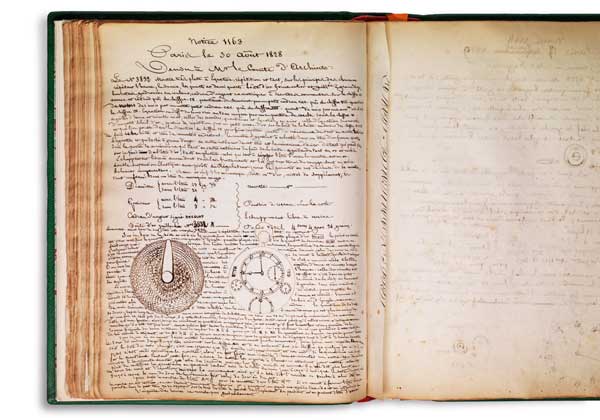

A fourth category of registers completes the archives: namely the certificates of authenticity of which the first still known dates from 1808. In this year, certain purchasers of watches and clocks were given a document termed an “invoice” bearing the name of the purchaser, the date of the sale, the description of the piece and all its details (diameter, thickness, type of dial, case number, type of escapement, total weight, etc.). In the case of complicated or unusual pieces, this “card” was accompanied by technical explanations and operating instructions for the different functions. In fact, it was not so much about guaranteeing the origin of the piece as about describing it in great detail and explaining how it worked. This aspect brings to mind the following anecdote: it was upon reading these certificates that yours truly rediscovered an invention by Breguet that had fallen into oblivion – namely “keyless winding”, or in other words, the modern winding mechanism. The following sentence, appearing in n° 1290 technical explanations describing Breguet’s n° 4952 watch sold to Count Charles de l’Espine on December 30th 1830, is unequivocal: to wind the watch (…), simply use the index finger and thumb to turn the gold knurled button in the pendant, continuing to twirl these button between the fingers until one feels it stop.

This type of document was very useful for the owner of the watch as well as for the watchmakers required to service or repair it. Given the international nature of his clientele, Breguet was completely aware that clients might not always be able to come to him and, with his characteristic concern for organization, he set up a network of watchmakers capable of “touching” his watches. It was in this way, for example, that in 1818, the following annotation appeared on the certificates: in the event of an accident occurring involving my watches, please consult:

- in London, Mr. Fatton, New Bond Street 92

- in Madrid, Mr. Charost

- in Moscow, Mr. Ferrier

- in Constantinople Mr. Leroy at Péralès Constantinople

- in Petersburg, Mr. Wenham, at the Livio brothers company

- in Vienna, Mr. Holzman father & son, n° 140 Rouge Street

At the end of the 19th century, a clear evolution can be seen, since the certificates are less and less concerned with new models. This period witnessed the advent of certificates issued for historical models, at the request of collectors. This activity of conducting appraisals and issuing certificates of authenticity has continued to today. In addition to the registers that we have just described, one might also mention the important book “for commissions” – or in other words, for special orders, the very one that features a request for a watch “pour brasselet” (for a bracelet) ordered in 1810 by Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples, as well as the inventories.

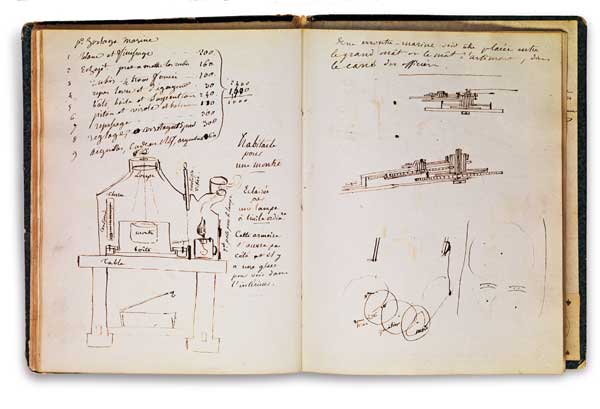

In addition, the Breguet archives also consist of many other documents: client letters which are an invaluable source of information on the type of and quality of relationships the great watchmaker had with his clients; workshop booklets, a great number of technical notes, very often scattered, written in the hand of Abraham-Louis Breguet or his son Antoine-Louis; and, not to be overlooked, the famous whole chapters of the Traité d’ horlogerie (Watchmaking Treatise) that Breguet developed and did not have time to finish, almost completed chapters acquired in 2010 to enrich an already remarkable collection.

Far from being static documents, these different archives delight the historians who consult them. As we have seen, they constitute an important tool in grasping the various

Various aspects of the life of the company and in establishing certificates of authenticity. They have played and continue to play a role in writing the history of the Breguet company that still harbors many aspects worthy of future research. The Breguet archives have kept step with the rhythm of the history of Paris as well as with that of the company they reflect. They have survived revolutions, moves, changes in ownership, wars, and, as well, economic crises, and their ability to withstand the twists and turns of fate commands admiration. Moreover, these archives are extended today with the printed registers of contemporary production that will one day in turn become historical documents!