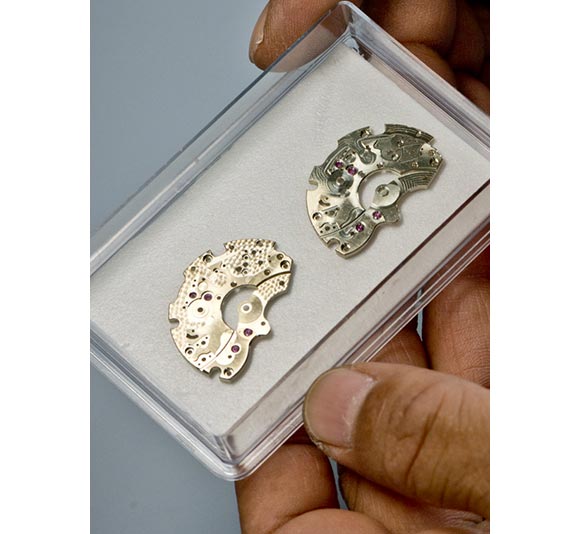

Every year, more than 10 million metal components are produced in Patek Philippe’s manufacturing workshops. Together, they make up a range of more than 15 different base movements, plus a number of complications. What is special about them is that they are all made according to a single philosophy: excellence. In order to achieve excellence, every single component is worked on by human hands. The parts emerge from the machines unfinished; they are precisely made but raw – mere three-dimensional shapes hacked out of soulless metal bars and plates. However, a series of subsequent stages infuses them with meaning, beauty and an identity. These stages, all considered forms of “finishing”, involve a variety of processes and skills. The aim of all of these procedures is to eradicate all traces of the manufacturing process (scratches, abrasions, oils, burrs) and make the surface visually perfect. But before beauty comes precision: each component must match the specifications, down to the nearest micron. Nevertheless, finishing is not a purely cosmetic procedure, it is fundamentally technical.

Finishing, in fact, is far from frivolous; it goes to the very heart of fine watchmaking. In Patek Philippe’s view, the quality of finish is inseparable from the quality of the watch – a principle enshrined in the company’s own certification guarantee, the Patek Philippe Hallmark. According to this exacting standard, every component of the movement (with the exception of the balance springs and barrel springs, which are in their own category) must be deburred to eliminate machining impurities. Depending on their location in the movement, the parts are then either brushed, circular-grained, polished, snailed, smoothed or countersunk. Smoothing involves creating an extremely fine-grained brushed finish. Polishing is a process of buffing the surface until it shines, sometimes to such a degree that it reflects light like a mirror. Circular-graining, used on the movement plates, is the process of carving a series of small overlapping circles.

Brushing is often applied to the sides of the components, creating an effect similar to smoothing. Countersinking is the process of chamfering and polishing the edges of every perforation. Finally, snailing is a brushed finish applied in concentric circles. The famous Geneva striping consists of wide bands of parallel curved grooves. In addition to these operations, all the components are chamfered: when they emerge from the machine, they are planed and filed, and then the neatened edges are ground at an angle to make them shine and catch the eye.

These are all considered traditional watchmaking finishes, and are not exclusive to Patek Philippe. Where Patek Philippe differs from other watchmakers, however, is in the number and variety of finishes used, their systematic application to every component, and the fact that they are all done by hand. Machine tools are used, but they are guided by human hands. Patek Philippe parts are not finished by computer-controlled machines, but by men and women. And, in most cases, motorised tools are eschewed in favour of metal files, wooden buffers, boxwood dowels and emery paper. And this is the case whatever the size of the component: a 30 mm diameter baseplate perforated with 80 holes comprising 12 different levels; a screw head one millimetre across; or a steel spring the thickness of a human hair.

Watch the video below to learn more on hand-finishing work at Patek Philippe:

And visit Patek Philippe's website dedicated to hand-finishing.