Our most recent look at the newly launched Patek Philippe ref. 5470 1/10th Second Monopusher Chronograph dealt with the precision mechanisms built into the cal. CH 29-535 PS 1/10, while our first chapter discussed the context and function of the watch. Having covered almost all relevant aspects of this watch, there is one last question that remains to be answered. The very nature of a precise tenths-of-a-second display calls for parts that are extremely fine, which leads to a mechanical paradox. How can you guarantee precision (which demands stability and robustness) in a mechanism that is inherently delicate?

To this end, the Patek Philippe movement developers have introduced a whole phalanx of mechanical security systems that act on various parts of the chronograph component assembly, protecting its most vulnerable points.

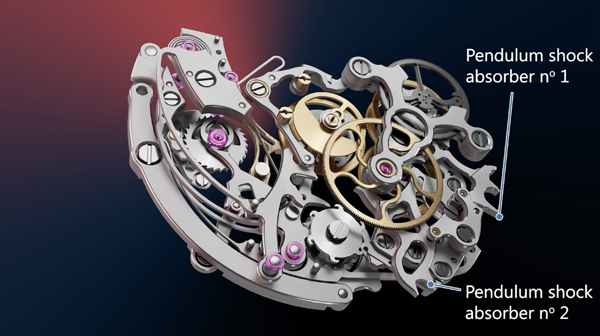

In any classically constructed chronograph, the column wheel is considered the control centre — its rotational position determines whether the chronograph is active or stopped. In a monopusher chronograph, which the ref. 5470 is, the column wheel also controls the zero-reset function. Usually, the rotational position of the column wheel is secured with a jumper spring, so that if the watch is subject to a physical shock of some kind, the column wheel still remains in its intended rotational position. In the cal. CH 29-535 PS 1/10, an additional level is integrated within the column wheel, on top of the ratchet gear toothing (lowest level) that allows the column wheel to turn in a controlled way and the columns (second level) that determine the running/stopped/reset status of the chronograph.

This additional level consists of a halo of notches, designed to engage with a corresponding hook on the main chronograph lever. When the chronograph is activated, the chronograph lever hook clicks into place within one of the column wheel notches. In this way, even if a physical shock manages to dislodge the traditional security elements (column wheel advancing lever and column wheel jumper spring), the column wheel is unable to rotate in the direction (specifically, the anti-clockwise direction) that could cause potentially catastrophic damage to the other chronograph components.

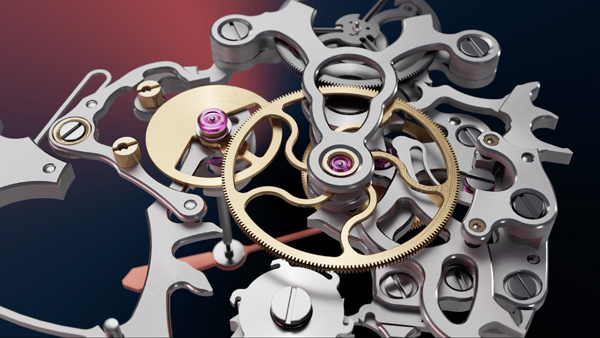

Particular attention has been paid to the engagement point between the intermediate tenths-of-a-second chronograph wheel and the tenths-of-a-second chronograph hand pinion. Because of how small the teeth on this pinion are, the slightest jolt could cause the tenths-of-a-second chronograph wheel (visible as the large brass wheel with serpentine spokes on the uppermost level of the movement) to separate momentarily from the tenths-of-a-second chronograph hand pinion (hidden beneath the central chronograph bridge) and allow the tenths-of-a-second chronograph hand to turn freely and lose its correct position on the dial. There is less chance of this happening with larger wheels, which generally have larger teeth and thus have deeper, more secure, gear engagement.

The Patek Philippe movement developers have therefore devised an array of shock absorbers, or more accurately shock compensators, to keep the tenths-of-a-second chronograph wheel pressed against the tenths-of-a-second chronograph pinion. These shock compensators have been specifically engineered in terms of form and mass so that even as they are subject to the same directional shock that would lead to the tenths-of-a-second chronograph wheel disengaging from the tenths-of-a-second chronograph hand pinion, the way they are shaped and pivoted causes them to push back against the tenth-of-a-second chronograph wheel, maintaining the essential engagement between wheel and pinion.

When I was a kid in the passenger seat of my mother’s car, she would occasionally be obliged to brake or switch lanes abruptly. (This is by no means a reinforcement of tired stereotypes about women drivers; my mother is an excellent driver and any unexpected braking or swerving on her part was always the fault of some other idiot on the road.) Anytime this happened, her arm would reflexively shoot out and pin me back against my seat, preventing my tiny frame from rocketing around within the confines of the designed-for-adults seatbelt. Now imagine little Suzie replaced by the tenths-of-a-second chronograph mechanism, and my mother’s arm replaced by the reengineered geometries of said mechanism’s components. The latter limits the motion of the former in cases of abrupt spatial displacement. If you feel comforted by the idea of having a mother’s protective arm around the most vulnerable parts of a watch, hurrah! That is exactly the effect I wanted to achieve.

The new Patek Philippe ref. 5470 1/10th Second Monopusher Chronograh, powered by the cal. CH 29-535 PS 1/10, is a remarkable assembly of microengineering that approaches the subject of a high-frequency chronograph from all possible angles — readability, mechanical innovation, power management, display precision and movement security. Going fast takes more than just speed. It takes a whole range of related skills and knowledge — and it goes without saying that Patek Philippe is on top of it all.

If you missed part 2, click here.